How can one describe a future society which by its very nature will break away from everything familiar to us?

- Image via Wikipedia

If there one question that gets asked ridiculously often to anarchists is to describe how the future society would look like, how would an anarchistic world function. Any answer given to this question can but only raise more questions and open more venues for criticism as any system described can only be simplistic and full of conceptual holes. Therefore I dislike this question with a passion, as not only it is commonly used as a basis for dismissal of anarchism without bothering to look any deeper but also misses the greater point that anarchism is about the process rather than the end result.

However today I had a small epiphany on this topic while watching the excellent BBC documentary The Secret Life of Chaos. At some point in the film, Prof. Al Khalili made the point that while migrating birds have no leaders and no complex system of organization or rules to guide their flights, their flocks nevertheless not only manage to achieve great feats such as flying over whole continents but also display stunning patterns of flight formations, surprisingly suitable for their purpose (such as flying in a V-shape formation) or simply beautiful, while managing to avoid even colliding with each other.

What surprised me about this statement is how incredibly similar this type of organization sounds to an anarchist society. A society which has no leaders and no complex rules and yet manages to function and even create a very complex societal organization and order which serves to maximize the happiness of every human within it. The complexity of it arises, not despite the simple rules underlying the system but because of them and the existence of chaos. In short because of the natural complexity that arises when one combines simple rules with feedback.

And human societies, if anything, are nothing but feedback.

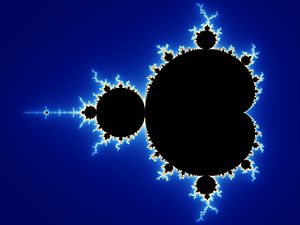

And this, I realized, is why one can never describe an anarchistic society. The simple fact of humans starting to follow simple anarchistic rules will create such levels of complexity and radical, strange and wonderful patterns and formations of social organization, that any prediction one of us makes now can only end up horribly wrong. In fact, the only accurate prediction one can make about a system that follows a certain set of rules within a chaotic environment is…that the system will follow those rules. Nothing else. You cannot predict the end result any more than one can predict the shape a flock of birds will take or how a certain pattern will look like when zooming 10x in a Mandelbrot set, while starting at a random location.

What does this mean? That any targets we set for a future society, such as the end of crime or having conquered the galaxy with billions of human colonies is impossible to predict with any certainty. No matter the system we setup to achieve this, because the smallest changes in our environment and behaviour will radically change what we expect. Just look at how science fiction looked even a mere 100 years ago (not to mention even longer) and you will see how little resemblance it has to our world. In fact, even looking at popular conceptions of the future, as crystalized in various movies produced a mere 30 years ago we can see that most of them are way off base. Personally, I’m still waiting for the flying cars.

And yet, even 30 years ago, nobody could even imagine something like the internet and how it would completely revolutionize our whole way of thinking and interacting with each other.

And yet, when one simple technological innovation completely re-shapes significant parts whole world in one short generation, you ask us to describe how an anarchist society, which would require a whole change of social relations, not to mention technology and lifestyle – in the face of rapid climate change and disentanglement from oil – would look like?! This is simply impossible.

However we can predict one thing: An Anarchy, that is, a society where humans individually follow and promote anarchist principles will…have anarchist principles. Simple nü?

So let me clarify this. One of the most fundamental anarchist principles is true democracy; the very simple concept that the power of one to affect a decision should be directly proportional to how much that decision affects them. As far as social rules go, this is as simple as “One person – One vote” or “The King’s choice is infallible”. We cannot remotely predict how a society based on this rule will look like any more than classical Greek democrats could ever foresee the US political system. What we can predict though is that the society will at its core allow people to have a truly democratic voice in their lives and thus greater control. Such a society would be definition need to have all hierarchies abolished (and that includes for example prison and business hierarchies) and will not have any prohibition on recreational drugs of any sort.

The rule is simple but the society that will form around it will be incredibly complex and impossible to predict.

This, I realize, is the only way to think about societal change. There is no point making utopian constructions in one’s head about how a future society must function for all humans to be happy, as this is moored in current social relations and current technological levels. This is the fatal flaw all such ideas had, from communist Utopias to “anarcho”-capitalist conceptions of freed markets and competing defence organizations. They assume a static world and a have a distinctly “Newtonian” understanding of social sciences. They assume that they have discovered the perfect equation which will bring about the perfect society…if only humans were smart enough to follow it to the letter.

But no matter how smart humans are the end result predicted is impossible. Not only because of minor, minuscule changes in the system (not to speak of major changes such as a new revolutionary technology being innovated), but fundamentally because of feedback, the end utopia will never come to be. All one will end up with is a vague trace of the original idea, somewhere in the developing society. Much like someone, paying very close attention, might discern the flame of a candle as it is moved within a video-feedback system.

In fact, our current society is nothing more than the end result of humans following a host of other basic rules of organization such as respect of free speech, respect for private property, promotion of classical freedom (i.e. your rights end where my rights begin), “one person-one vote”, secularism, gender and race equality, promotion of and respect for the scientific method and many others ((If you thought it’s merely very difficult to predict a future society based on only 1 rule, I want to see you juggle 5 or 10)). However, society did not change overnight, we did not move from feudalism to capitalism in one month, nor did we embrace modern science in a few years. It took centuries for those ideas to become mainstream because of the societal evolution. And those ideas only even got a hold in the first place because of the same evolution that came before them. Because of the way the system ended up forming from the ideas that were dominant in the past. And the funny thing is that those ideas might have been the complete opposite of what they produced.

What this means is that while we may have reached where we are because of the ideals that came before us, the capitalist mode of production which came after feudalism and slavery, which came after theocracy which came after imperialism and so on, we are still capable of changing where we are headed by the simple act of embracing different ideals. We will not know how exactly we will turn out, but we will know that we’ll have those ideas in action ((that is, unless there are no conflicting ideals as well. In fact, this is why we cannot have a free society or even one that is simply gender or race egalitarian. Those conflict with respect for private property and respect for authority which breeds hierarchies and thus perpetuates patriarchy minority oppression)) and thus can rule at least the things out that conflict with them.

In the end, the order of human societies are the complex result of simple rules, much like chaos theory predicts. However there is a factor which is absent from every other chaotic system we see around us. A simple detail which gives a whole new dimension of complexity to the evolutionary progress:

Humans can modify their own environment.

This simple fact I have come to realize is surprisingly important. Whereas every other organism (or simple pattern) can only adapt to how the environment around it changes and will only slowly change its basic rules as a result of natural selection, humans can to a large extent modify both their behaviour and their social rules instantly (in an evolutionary timescale) by using their primary trait, their reason, to discover a better optimal path than the one they were following until then. This means that they can follow a particular rule-set until it stalls or it becomes obvious that it is detrimental and then either modify their environment until this is not the case anymore, or simply discard their rule set for a superior one ((Of course, by going one level of abstraction back, this human ability to modify their environment and behaviour is only the result of evolution again, which has granted the humans the best capacity to expand their number given the nature of the planet and the universe as a whole))

Looking back at human history from this perspective, it’s impossible to miss this process. Humans adapted to their environment by using a specific system of social organization and production. When their environment changed (say by the introduction of a new technology or resource) they changed then either or both of them accordingly. Thus the slavery as a mode of production led to Imperialism (as well as, surprisingly, Democracy in classical Greece – remember the things we can’t predict?). The discovery of the steam engine and oil and the general industrial revolution led to the widespread abolition of slavery in favour of wage-slavery.All these things happened not because of fate, or the will of a creator and whatnot, but because of simple rules and material changes and feedback which always worked mindlessly to create the best combination of social organization given the existing environment for the maximal human spread.

And this is in fact the crux of the cookie. The current socioeconomic framework is not optimal anymore. The environment has changed far too much since the dawn of capitalism. Not only has the technological level broken the barriers of the system and thus made the ground fertile for different organizations (much like the industrial revolution made slavery sub-optimal) but the way the environment changes because of the system (such as global climate change and peak oil) has made the current one not only simply detrimental but outright destructive for the evolutionary success of humans (i.e. our continued existence as a species).

And this is where Anarchism comes in. I can only but consider it but the latest of an human societal recalibration required to work with the current and changing environment. It is no wonder than the first flickers of the idea occurred just as the capitalist system completed its dominance as the chosen method of production. It’s as if human history cunningly winks at us, while it hints to what is to follow. In fact, I consider it even more noteworthy that anarchist theorists had intuitively grasped the chaotic nature of social change approximately half a century before Turing made his breakthrough research into biological patterns. If there’s one thing that has always been a primary concept behind the anarchist movement is how it gives far more weight to the means to achieve change than it does to the ends. For me at least, the more I learn, the more this fact is solidified and the current post is only the latest of such knowledge.

Is Anarchism (or Marx’s “Pure Communism) to be the last sociopolitical stage? I used to think so but now, highly doubt it. As much as we can’t even remotely predict the future, so can we not predict the circumstances that might make Anarchism obsolete. Perhaps it will be enough to save us from annihilation by our own hands but not enough to survive contact with Alien races. Who knows? As much as Adam Smith could not even imagine a system like Anarchism when the Free Markets he suggested was itself a radical concept, so can I not even imagine what could possibly follow Anarchism.

But what I do know, is that no anarchist will be ever be able to accurately describe what Anarchy will look like. Only that like a flock of birds, it will be complex in its simplicity.

Anarchy is Order.

And Order comes from Chaos…

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?w=980)

"This is not strictly about self-generating goods. It is about having enough goods so that the price, due to supply, drops to (nearly) zero. Even when such thing would be overwhelmingly positive for the whole of humanity, as in the case of food or shelter, for capitalism this is negative."

Low prices is not negative for capitalism. Negative for capitalism means preventing the flow of resources to their most productive spot (i.e. preventing economic agents from acting freely). High or low prices aren't good or bad for capitalism. They may be good or bad for certain businessmen (who aren't necessarily believers in capitalism). Extremely low food prices would mean resources would be freed up from food production to move to where it is better used by free economic agents. What this means, then, in relationship to…

"It may very well be the case that we may never reach this level of production (although the rising production per worker in the modern day points otherwise) but we’re talking that if it were possible, it would not be even feasible under capitalism."

…is that it's only not feasible if all free economic agents find a more profitable use of there money than producing food that costs almost nothing to produce. Profitable isn't limited to monetary terms, either. So you could say it's only not possible if no one cares to give food to those who are unable to afford it.

As for intellectual "property," it is not a part of capitalism, as it is a form of government imposed monopoly on ideas.

Perhaps, but the reason I only get as specific as I do is that the particulars of valuing effort might change with technology and from job to job. Albert/Hahnel suggest labor hours and co-worker ratings subject to adjudication. However, for some jobs and technological levels, more reliable measures might include sweat, brain activity, output, and/or output over input. For still others, it might be more useful to disregard effort.

All those things are based on a fetishism of "fairness" which in turn ends up with people distrusting and competing with each other rather than co-operating. Labour-hours, co-worker rating (augh!) and other stuff is unnecessart. Co-workers can see immediately when someone is slacking off and peer-pressure them to change their ways. As long as people can get the job done, all these shit is unnecessary and will only cause harm.

If you’re right that peer pressure is so powerful, labor hours and coworker ratings will equalize anyway, making it a moot point. In fact, both can be opt-in, only submitted in case of failure of peer pressure and, perhaps, exceptional effort. Also, it’s inefficient to waste labor and leisure hours on peer pressure, not to mention unjust: if I want to work less and less hard in exchange for fewer credits, that’s my business, not yours. And how peer pressure in response to slack is any less “fetishistic” about fairness than docking credits, requires explanation.

Thanks for writing this. Now I have somewhere to link to when I get that question.

I have been wanting to write a post on fear of chaos. That really seems to be the basic stumbling block for most people. And responding to that fear with elaborate plans like Parecon always seemed useless to me. I haven't quite figured out how to approach that fear, that need for the illusion of control.

What "illusion of control"? Parecon certainly reduces oppressive uncertainty, but it's not like it claims to predict earthquakes.

There's a fun Mises talk on the history of Socialism by Salerno where he mentions the forerunners of Marx (Fourier, etc) that were basically crazy, and had these detailed plans even specifying how many people would live in a housing unit for how "utopia" would work. Then Marx came along and "rescued" socialism from these religious loons, by giving it some scientific backing.

actually the name of the "chaos" theory you are describing is called "Emergence" wikipedia has a brilliant article about it and loads of poeple are doing research on it, also there is a nice article i read the other day which was entitled "the man who looked into facebooks soul" but it mentions some very interesting ideas about the aggregation and analysis of various types of data finding that people basically votes hundreds of times a day as they go about thier normal business of sending and replying to messages and bookmarking websites and contacting friends and organizations, shopping etc. and that perhaps it is theoretically possible that all of these small votes be counted, and that perhaps someday they will be……but as you said who knows how this will end up working out or what it will be used for

Well emergence has more to do with the order that arises out of chaos, not the chaos theory itself. In short, emergence is the reason why an anarchist society will have order and complexity. Chaos is why we can't predict how it will look like.

Your text translated to lithuanian and published in lithuanian anarchists portal:

http://www.anarchija.lt/index.php/teorija/21076-k…

Good work, Konstantine.

Heh, cool. Cheers!

I strongly disagree, especially to the extent that Broadsnark's comment is concurrent. If "any" answer to the title of your entry leaves Anarchism as vulnerable to criticism as before, then there's a serious problem with Anarchism. The very notion of Anarchist society (pre-vision) is simplistic, in that, just as there was never any society that adhered absolutely to Capitalist or Feudal rules, none will ever adhere exactly to even the basic principle(s) of Anarchism. In fact, when people ask you to paint them an Anarchist picture, they're often saying, "Give me one good reason why people should initiate, or would tolerate, Anarchism." They want precisely to "look deeper", and you should help them.

I believe there was a more recent study that concluded that birds in the air actually do have leadership (albeit rational as opposed to ordinal), those more influential in decision-making tending toward the front of the formations. Regardless, it's the result of evolution on, as you say, an "evolutionary time scale", of which we don't even have one left. Sure, our reason helps, but we were reasoning even in the days of slavery, the product of allegience to a subset of the laws of Anarchism: the Laws of Nature. But then, you seem to be flirting with a sort of Nihilist's Social Darwinism, even rationalizing Slavery with all it did for Democracy internal to one dominant class (perhaps I'm being unfair here).

I'm not sure that Proudhon's Possession can be reconciled with the Affectedness principle you stress here. It's not at all clear that a thing's possessor(s) is/are, even in the first instance, the most–much less only– one(s) affected by the relevant decisions. This may be the crux of it, as Proudhon's very different Anarchism might well be less predictable.

Parecon has its own particular usolvable problems primarily having to do with scaling.

Could you be more specific and identify the relevance? Two things are after all necessary for scaling problems:

a) pre-existing problem(s);

b) problems scaling solution(s) thereto.

It's thus easy to avoid economic scaling problems: ignore the pre-existing problems, delegating them billions of times, as in Proudhonian Anarchism (PA), to uncoordinated individuals. The only other thing PA has to offer is the arbitrary, historically blind, class-informed rule set it wants to govern human-to-human and human-to-nonhuman-to-human relations. I'll admit that such rules imply simpler decision trees than do more Nihilistic Individualisms, but, simplification not being their purpose, they do so insufficiently.

You're wrong that societies have not adhered absolutely to Capitalist or Feudal rules. Perhaps your mistake is that you think that those system include some principles which they don't. In fact however, both of them did adhere to their core ideals such as a wage-labour driven society for capitalism and landlordism & rent for Feudalism. As such, if one declares the core rules of an anarchist society to be quite specific, such as true democracy and possessive ownership for example, then you certainly guarantee that an anarchist society would include them by definition.

The good reasons therefore to initiate or tolerate anarchism is because such system would promote rules such as true democracy and possessive ownership. This would then extrapolate to other things that can also exist because of them, such as equality.

I certainly can help people "look deeper" but I'm not prepared to lie for it (i.e. describe a future society which I have no solid basis of being able to preconceive).

RE: Birds: It may be that but that still does not change the fact that the leadership appears spontaneously, voluntarily and chaotically. I.e. those who end up at the front are usually the result of luck rather than coercive force or rational choice. Among those who have the chance to lead for a bit, it is perhaps that those who have evolved the best "leadeship" instincts receive some credibility that can be remembered in the future (No idea about the capacity of birds to remember leadership and recognise an individual among a flock of thousands). But their formations and their exact behaviour is certainly the result of chaotic forces – evolution primarily, but individual choice secondary.

You are being unfair here. I especially said that just because a social system has evolved and taken place does not mean that humans need to stick to it if their reason tells them otherwise. And slaves did not accept their masters because of reason, but because of coercive force (in the form of the slaver's whip). The whole idea of such systems is that those who benefit from them. assert that they are the best and suppress the reasoning and arguments of those who try to explain why they are not. As such, they subdue the thing that catalyzes the rapid changes of human societal systems: feedback.

I suggest that anarchists not only should not suppress feedback but that they should nurture it (knowledge), promote it ( demoracy ) and allow it to bloom (freedom). You can't counter my argument by pointing out to systems which did the opposite of this!

Well, I think the best way to make your case here is to present an example where this might be the case and we can then analyze it.

It is still up to the subjects of PA to, as frequently as possible, estimate as useful a part of their own and others' decision trees as they can or suffer the consequences of what is, especially under Individualism, an unforgiving world. They still must, as continuously as possible, evaluate and assign as exact probabilities-of-occurrence to as-many-as-possible as-possible-as-possible possible futures as they can if they hope to inform such decisions in ways that will spare them what little, particularly under individualism, misery they can avoid. One could dedicate one's entire life to such strategizing and still come nowhere near optimality; but of course, under Individualism, most are compelled by competition to dedicate most if not all of their time to the EXECUTION of their consequently crudely-made decisions.

Parecon eases the individual burden by consolidating the billions of individual economies into a collective one with a billions-strong team of organized economists. Its results' sub-optimality is related to scale, but so are individual planning mechanisms' related to scale (the actually and potentially accessible world's, mind you, not merely the individual's). The more complex such world, the more labor-intensive, costly, specialized, ignorant or undetailed planning must become. The Parecon for running South End Press is thus quite different from the Parecon for running a country, and I'm not the first Pareconist to say so.

Another simplifier of decision-making is poverty. PA's abolition of wages and rents would split society into two categories:

a) a shrinking class of possessors of quickly increasingly automated capital;

b) an enlarging one of increasingly dispossessed service workers and jobless folk.

Initially, the economy would be generally and superoptimally dedicated to the aforementioned automation. Gradually, though, that stage would give way to a second, which would further split the workforce into three subclasses:

a) machines, used mainly for capital-intensive production;

b) females, used mainly for sexual gratification;

c) men, used mainly for whatever other services were still worthy of sustenance fees, as well as blood, sperm, and organs.

The final stage would be the death of the human race. The remaining Possessor(s) would have worked their species-folk to obsolescence, machines now being capable of all their old services. But by then, choice would have long since become an historical concept for most, and associated scaling problems with it.

I fail to see the connection between Possession and equality. For an extreme example, consider a disabled orphan. Incapable of equally Possessing, how would she acquire equality? If by the kindness of strangers, then why not make that kindness systemic (identify her as the owner, PRIOR TO PRODUCTION AND EVEN ALLOCATION OF MEANS THEREOF, of a share of consumption proportional to her need or, if her the product of her work is considered worth the product of her volition (called "effort and sacrifice"), that, as in Parecon) and so cut out the middle man? As for the difference between affectedness and possession, let's stick with the her. You don't think she's affected by the decision of whether or not to do her that kindness?

The problem is that Parecon attempts to replace chaotic action and emergent order with chaotic action and planned order. Somehow believing that having a lot of distributed planners instead of a few ones can do a better job of planning an economy. It's all well and good of talking about "billions-strong team of organized economists" but I have no idea what the practical significance of this is or how a billion people are going to communicate together to plan a BJC for billions of jobs and billions of people.

Of course a lot of planners can do a better job than a few. Haven't you ever heard of feedback? I know you have, because you talk about it constantly. The differences between Parecon's feedback and "chaotic" feedback are that Parecon's:

a) occurs prior to the commitment of resources, thus eliminating the waste inherent to ex post facto correction;

b) costs nothing and thus can be iterated indefinitely;

c) has as the only exceptions to its egalitarianism conditioners of volition per se, so as not to needlessly diminish marginal utility.

However the many planner also increase the wasteful task of planning as they then have to find a way to coordinate all their distributed planning. I fail to see how that would work without huge waste. Whereas a chaotic system leaves the planning to self-management and democtaric decision making when required, Parecon seem to devolve into a bureaucratic nightmare.

Also you're confused a bit I believe. Parecon also is a chaotic system, much like all human systems. Both have feedback which allows for emergent order. The problem does not come from this, it comes from the difficulty of having billions coordinate billions instead of billions coordinating themselves.

I can't figure out what's more of an exaggeration: "billions coordinate billions" or "billions coordinating themselves". Parecon would have facilitators just as workers' factories and peasants' farms have managers and representatives and would presumably continue to under mutualism. Yes, whenever people can afford it, they turn to specialists. Even wealthy individuals hire business consultants and even life coaches. The reason is simple: optimally managing what one owns, even if that's only oneself, is not. Coordination, though the difficulty of achieving it is also related to its scale, MAKES PREDICTION EASIER in relation to scale by enforcing so many humans' action. Do you have any game theoretical or empirical reason for supposing the coordination problem outweighs the prediction problem, or is it a hunch?

I can't figure out what's more of an exaggeration: "billions coordinate billions" or "billions coordinating themselves". Parecon would have facilitators just as workers' factories and peasants' farms have managers and representatives and would presumably continue to under mutualism. Yes, whenever people can afford it, they turn to specialists. Even wealthy individuals hire business consultants and even life coaches. The reason is simple: optimally managing what one owns, even if that's only oneself, is not. Coordination, though the difficulty of achieving it is also related to its scale, MAKES PREDICTION EASIER in relation to scale by enforcing so many humans' action. Do you have any game theoretical or empirical reason for supposing the coordination problem outweighs the prediction problem, or is it a hunch?

These were your own words.

Again you're arguing against mutualism.

In any case, no, it does not go without saying that factories and farms would have managers. And a mandated representative is not a manager either.

You seem to have swallowed the myth of Capitalist economics that managers increase productivity. I suggest you rethink this proposition which has been proven wrong by worker-run businesses and self-managed factories.

No, my words were “billions of coordinated economists.” The coordination would be done, in the last instance, by the combined efforts of computers and facilitators.

You’re wrong about workers’ factories, incidentally. Just as soldiers‘ armies have officers, they have representatives and facilitators as a matter of course. I worked in a factory for years, and I‘m quite sure that if you had you would agree that to fail to delegate such tasks would be intolerably disruptive. No, what distinguishes workers’ enterprises from capitalists’ is that the former’s representatives and facilitators are answerable to the workers. Similarly, Parecon’s facilitators are answerable to the society. And no, Parecon doesn’t mandate them. But it is predictable that society would approve of such jobs rather than prolong the planning period by leaving it entirely up to computers.

Sorry, but the more you explain about Parecon, the more I'm convinced that it sounds like a bureaucratic nightmare when scaled.

I do not dispute that. But Coordination is not something that only Parecon can do. Especially since you mentioned that this will be done through the price mechanism, which is similar to what mutualists suggest. I don't think there's any Anarchist theory which rejects coordination of some kind, whether through the price mechanism and competition or via councils&syndicates and cooperation. The only thing that Parecon seems to do is add an extra layer of bureaucratic cooperation over the price mechanism and asser that this makes it superior. I remain unconvinced that this will not simply introduce waste as it won't be able to scale.

What you call bureaucracy is precisely democracy. Mutualism avoids such “bureaucracy” by being dictatorial with respect to any given property (Proudhon’s “property is theft” referred specifically to absentee ownership; he considered possession a type of property too, hence “property is freedom“). Yes, democracy is a drag; so is having to get a woman‘s consent before you have sex with her.

What nice rhetoric. It reminds me of Bolsheviks declaring that the dictatorship of their party was an expression of "democracy".

Parecon‘s price mechanism is just one contributor to its predictive power. Another is planning. Capitalism has always had a price mechanism, and it’s always had crashes and been inefficient even within its own income distribution; why? Because no one can count on anyone. Mutualism is no different in that respect. Under Parecon, by contrast, you don’t have to waste resources and opportunities on risk aversion, because production and consumption are guaranteed by each other‘s plans.

I understand the theoretical idea of parecon. I'm just saying that it's impractical as it doesn't scale. I have seen no convincing arguments that it does. At this point its feasibility is on a theoretical level and in my mind, is about as likely to work as propertarian free markets or governmental communism. Those work in theory too btw.

And again, not all price mechanisms are equally informative. For one thing, reiteration is key. Take the extreme, singular case of simply a seller setting a price and a shopper choosing whether to buy. What does the outcome tell you? Not much. Particularly, it only tells you whether the shopper prefers the status quo or having the object and that much less money. Only in case of reiteration does a more comprehensive account of shopper’s preferences regarding that object reveal itself. The problem is, each time the buyer buys, he loses both his need of the object and his means of revealing it. The frequency of iterations is thus constrained in markets. In Parecon, by contrast, the number of iterations is independent of the number of transfers, unconstrained.

Very nicely put but I have no idea what this means in practice. How does this pareconist "reiteration" cover up for the lack of a full information of market exchanges?

These were your own words.

Again you're arguing against mutualism.

In any case, no, it does not go without saying that factories and farms would have managers. And a mandated representative is not a manager either.

You seem to have swallowed the myth of Capitalist economics that managers increase productivity. I suggest you rethink this proposition which has been proven wrong by worker-run businesses and self-managed factories.

The primary way to coordinate the distributed planning has already been found: the automatic price mechanism. Yes, some coordination-by-humans would take place, but is there anything that POSITIVELY (not just failing to see why not) makes you think such coordination would be more wasteful than the waste (including coordinative waste) inherent to fundamentally unplanned economics, part of which I've identified? And if so, is that difference in waste more important that the inequality inherent to individual ownership? That last one is a judgment call in that you will be judged bourgeois if you choose wrong.

The price mechanism assumes competition between producers. Is this really what Parecon suggests? The embracing of a sub-optimal tactic (competition) over the one that comes more naturally to humans (co-operation)? Furthermore, if you are basing yourself on the price mechanism, and money, then you can fall prey to all the pitfalls that follow from those.

Parecon's price mechanism is cooperative and involves credits, not money. The pitfalls you have in mind are almost certainly the province of the existing price mechanism.

Parecon's price mechanism is cooperative and involves credits, not money. The pitfalls you have in mind are almost certainly the province of the existing price mechanism.

I don't know so much about Parecon so I'll take you at your word. However since you're using words such as "money", "profit" and "price" it is only natural that you're talking about these concepts as commonly understood. If you mean something else by those words, I think it would be better if Parecon used some other word which fits better.

I think it would make it far more wasteful than unplanned economics which do not use price mechanisms, such as communism based on pure supply and demand according to ability and need.

I've never heard of that branch of communism. Does it have a name? It appears self-contradictory.

You've never head of the "branch" of communism that suggests "From each according to ability, to each according to need?" I don't think there's a "branch" in fact that does not suggest this…

You've never head of the "branch" of communism that suggests "From each according to ability, to each according to need?" I don't think there's a "branch" in fact that does not suggest this…

I'm not convinced that a possessive system will introduce inequalities based on individual ownership. Once people cannot own more than they can use, they have no reason to hoard and therefore introduce inequality.

"Reason" to hoard or right to hoard? Either way, hoarding isn't necessary for inequality, so a possessive system would incompletely eliminate inequality. And instead of doing so rationally, such as via progressive taxation, the possessive system would effect suboptimal men-for-the-job, as people would be "hired" based not on their qualifications but on the size of their bids.

"Reason" to hoard or right to hoard? Either way, hoarding isn't necessary for inequality, so a possessive system would incompletely eliminate inequality. And instead of doing so rationally, such as via progressive taxation, the possessive system would effect suboptimal men-for-the-job, as people would be "hired" based not on their qualifications but on the size of their bids.

I do not see how. In a possessive system, people do not need to bid for jobs. They can simply choose the ones that fit their talents better because they would get to keep the full value of their labour. Your argument makes no sense.

I realize that Parecon's superior feedback system doesn't help your case, but I'll appeal to your sense of objectivity and urge you to give it its due. Whereas unplanned economies allow for emergent order on an "evolutionary time scale", Parecon achieves it in a matter of weeks (more or less, depending on your skepticism); whereas unplanned economies only get feedback when resources are literally wasted, Parecon's feedback is a matter of implied future waste, which correction averts; whereas individual economics receive feedback largely in proportion to wealth, luck and natural talent, Parecon, combining the law of diminishing marginal utility with acknowledgment of human likeness, strays from equality only where it can be positively justified.

False. Emergent order does not arrive on an evolutionary time scale. While it is evolutionary, it progresses far more rapidly and I haven't seen any argument that Parecon would speed this up rather than slow it down with unnecessary bureaucracy.

False. Given supply and demand separated from the quest for profit and the price mechanism, waste is practically eliminated, without having to introduce bureaucratic waste instead.

I'm not saying that Parecon is not better than Capitalism. I'm saying that it's unlikely that it's better than Communism and I'm not convinced it's better than Mutualism.

"Individual economics" included Mutualism and, I'm sure, your "Communism".

I have no idea what you're trying to say but I don't appreciate your scare quotes.

…

Please. Don't declare superiority before you've made your case. It only makes you look arrogant.

False. Given supply and demand separated from the quest for profit and the price mechanism, waste is practically eliminated, without having to introduce bureaucratic waste instead.

Explain yourself. How would supply and demand be calculated, let alone coordinated, without neither bureaucracy nor a price mechanism?

You've got a warehouse with 100 spades in stock. The warehouse workers notice that there is a demand of 20 spades per week. They request a supply from the spade-production-syndicate for 20 spades per week. There you go.

You've got a warehouse with 100 spades in stock. The warehouse workers notice that there is a demand of 20 spades per week. They request a supply from the spade-production-syndicate for 20 spades per week. There you go.

This will not resolve the scaling problems of Parecon which are related to the problem of trying to create Balanced Job Complexes for an increasing number and diversity of jobs. While this may be possible when isolated within a small company and the roles within it, it quickly becomes impossible when trying to balance parecon within a community, not to mention a society.

PS: Please do not reply to your own comments. Either reply many times to the same comment if you've got multiple points to make, or put everything in one comment. Replying to your own comments makes it difficult for people to follow the discussion due to the threading.

sorry, I repeated the mistake before reading this, but I won't again.

Perhaps. You're likely correct as I'm not a fan of market economies in all forms anyway. However I'm not the person to defend mutualism (or "Proudhonian Anarchism" as you call it) as I do not espouse it.

Again, I'm not a mutualist so I'm not certain why you're brining this attack vector up. Even so however, I can see that your points do not follow. For example, why are workers dispossessed from their automated capital? The further 3 classification seem to be pulled out of thin air.

I can just as much foresee a sufficiently automated micro-production which would lead to every individual being self-sustainable given raw material and/or the splitting of productive tasks between individuals and families and the trade of commodities between them.

Possession facilitates equality. It is a necessary step before it in order to prevent accumulation.

Indeed, I am in favour of making kindness systemic. That's why I'm a communist in the first place.

I don't know what to make of that first line. Can you elaborate?

Without ownership being limited by occupancy or use, and rather being arbitrary, people can start accumulating wealth, particular wealth and capital. Since they do not need to use or live in it to be considered their owners, they can argue that they are within their rights to hire people to work their capital or land, therefore moving down the road of inequality.

I don't know what to make of that first line. Can you elaborate?

But automation will continue to occupy a superoptimal share of the creative economy; the capital-intensive worker will continue to die out until society consists of one nominal, button-pressing "possessor", in your terms, individual or family and those left whose services are worth their sustenance fees. As for the three subclasses, people under mutualism are only permitted to be fee-slaves, never wage-slaves, so they would be increasingly relegated to the service sector, which, it presumably being legal, prostitution would occupy a noteworthy place in. As for your fanciful egalitarian micro-production end, it sounds a lot like Adam Smith's prediction of how capitalism, left alone, would turn out–that is, wholly discredited. No, no set of rules of acquisition, holding and transfer can result in anything but monopoly. Now, to your credit, you admit that the rules should change if they become harmful, but who decides when they have? The possessors!? If so, change would never come; if not, you've writ a recipe for permanent civil war. Parecon avoids all this by its automatic resetting of relations.

a) planned in a second iterative planning stage, in which the jobs would be priced–again, largely automatically–purely with respect to empowerment (naturally, production planners would be expected to adjust expected input and output and/or facilitators expected surplusses and defecits and/or prices directly according to the inherent tenuousness of input/outputs of extremely empowered or unempowered production plans; but even this could be done largely automatically); b) internal to workplaces, with the only cross-workplace balancing being contingent on the personnel shuffling not adversely affecting production (this method, of course, needn't be socially planned at all, although it could be socially or communally supervised for the balancing of productive efficiency and balance itself).

Any socialist system is utlimately possessive. Even communists need to have an exclusive ownership claim on some items, such as their toothbrushes. The difference with a capitalist system is that ownership is defined by occupancy and use (i.e. "this is my toothbrush because I use it daily") and not by legalistic claims.

Again, I have to say that I am not sufficiently versed in mutualism to argue consicely against your scenario. My initial impression however is that you are taking the worst possible result and assert that it is the only likely scenario. It's just as likely in my impression that as production per labour-hour is increased, rather than having people work the same amount of hours for more goods, people will choose to work less. Furthermore, a technology such as universal 3D printering that would allow anyone possessing one to produce any commodity, including universal 3D printers would allow a self-sustenance at a low cost which would make the scenario of free slaves you posit impossible. Such a society would have self-reliant people who only trade in luxuries which they cannot produce themselves. It would avoid people becoming dispossessed.

In any case, I myself think that mutualism is unstable so I will not continue defending it. I just wanted to mention that your scenario seems dishonestly extreme and I would like to see you debate with a mutualist on it.

One reason the existing Parecon collectives typically use BJCs is because they have no need for the sophisticated planning system suggested by Parecon. A large-scale Parecon, by contrast, would benefit greatly from such system, and so would face the question of whether or not to compound its complexity with mandatory BJCs. Personally, I consider systematic BJCs somewhat superfluous in the light of the other empowering aspects of Parecon, so it's lucky the BJC is an entirely separable one. That said, it could be integrated into production planning, with plans specifying, in addition to expected input and output, expected work-hours for each category/order of empowerment. Empowerment would effect individual production prices in a way similar (largely automatic) to the way supply and demand would effect all production prices. Alternatively, BJCs could be posterior to production planning, being either:

a) planned in a second iterative planning stage, in which the jobs would be priced–again, largely automatically–purely with respect to empowerment (naturally, production planners would be expected to adjust expected input and output and/or facilitators expected surplusses and defecits and/or prices directly according to the inherent tenuousness of input/outputs of extremely empowered or unempowered production plans; but even this could be done largely automatically); b) internal to workplaces, with the only cross-workplace balancing being contingent on the personnel shuffling not adversely affecting production (this method, of course, needn't be socially planned at all, although it could be socially or communally supervised for the balancing of productive efficiency and balance itself).

From what I understand, what remaining mutualists there are are bound by unfalsifiable individualist ethics; the debate would reach an impasse very quickly.

Even if I'm taking the worst possible result, its one that's far more likely under mutualism (I do often call it "Proudhonian Anarchism" partly to distinguish it from minarchist and other mutualisms; I thank you for correcting me, however, as the anarchist aspect is probably irrelevant to this discussion) than under Collectivism, for the reasons mentioned. As for the other "likely scenario", I don't see it as particularly likely under mutualism. Firstly, it's only production PER PRODUCTIVE (or, more accurately, capital-intensive) LABOR-HOUR that's increased. Whatever capital-intensive jobs aren't lost to unemployment will be converted to less capital-intensive jobs, which tend to be more service-oriented. Production and production per labor-hour per se, will rather decrease. It stands to reason, then, that people will rather "choose" (be compelled) to work more hours, not less, if they're lucky enough to get them.

From what I understand, what remaining mutualists there are are bound by unfalsifiable individualist ethics; the debate would reach an impasse very quickly.

Even if I'm taking the worst possible result, its one that's far more likely under mutualism (I do often call it "Proudhonian Anarchism" partly to distinguish it from minarchist and other mutualisms; I thank you for correcting me, however, as the anarchist aspect is probably irrelevant to this discussion) than under Collectivism, for the reasons mentioned. As for the other "likely scenario", I don't see it as particularly likely under mutualism. Firstly, it's only production PER PRODUCTIVE (or, more accurately, capital-intensive) LABOR-HOUR that's increased. Whatever capital-intensive jobs aren't lost to unemployment will be converted to less capital-intensive jobs, which tend to be more service-oriented. Production and production per labor-hour per se, will rather decrease. It stands to reason, then, that people will rather "choose" (be compelled) to work more hours, not less, if they're lucky enough to get them.

I must admit I've never heard of universal 3D printering. I can't imagine it's very close at hand; nor can I imagine mutualism being particularly speedy at getting there (possessors, those with the means to do it, would be foolish to produce that which would make their advantage obsolete); nor would the dispossessed be able to afford it anyway; nor is mutualism+3Dprinters-for-all clearly preferable to Parecon+3Dprinters-for-all or any other system+3Dprinters-for-all.

I must admit I've never heard of universal 3D printering. I can't imagine it's very close at hand; nor can I imagine mutualism being particularly speedy at getting there (possessors, those with the means to do it, would be foolish to produce that which would make their advantage obsolete); nor would the dispossessed be able to afford it anyway; nor is mutualism+3Dprinters-for-all clearly preferable to Parecon+3Dprinters-for-all or any other system+3Dprinters-for-all.

Ahem. I meant to say 3D-Printing 🙂

It's closer than you think but it's still not revolutionary enough as a technology to have a big impart. At the moment, it's more at the level ENIAC was to the modern PC I would say.

A society without structure would be … anarchy.

From what I understand, what remaining mutualists there are are bound by unfalsifiable individualist ethics; the debate would reach an impasse very quickly.

Even if I'm taking the worst possible result, its one that's far more likely under mutualism (I do often call it "Proudhonian Anarchism" partly to distinguish it from minarchist and other mutualisms; I thank you for correcting me, however, as the anarchist aspect is probably irrelevant to this discussion) than under Collectivism, for the reasons mentioned. As for the other "likely scenario", I don't see it as particularly likely under mutualism. Firstly, it's only production PER PRODUCTIVE (or, more accurately, capital-intensive) LABOR-HOUR that's increased. Whatever capital-intensive jobs aren't lost to unemployment will be converted to less capital-intensive jobs, which tend to be more service-oriented. Production and production per labor-hour per se, will rather decrease. It stands to reason, then, that people will rather "choose" (be compelled) to work more hours, not less, if they're lucky enough to get them.

I must admit I've never heard of universal 3D printering. I can't imagine it's very close at hand; nor can I imagine mutualism being particularly speedy at getting there (possessors, those with the means to do it, would be foolish to produce that which would make their advantage obsolete); nor would the dispossessed be able to afford it anyway; nor is mutualism+3Dprinters-for-all clearly preferable to Parecon+3Dprinters-for-all or any other system+3Dprinters-for-all.

Under Collectivism (such as Parecon) and Communism, possession doesn't define ownership. The toothbrush is only yours because it's a consumption item you paid for with socially-administered credits or society says it is, respectively. Whether you use it, lend it, or hang it on the wall and pray to it is irrelevant. Thus, one's using, say, the only universal 3D printer daily, would be irrelevant. It would be collective property because of its productive nature or its being too expensive for individual purchase or its being deemed arbitrarily by society to be so.

I disagree. As long as there is a requirement for ownership (as all human systems must have) that ownership must be grounded on something to avoid being just an arbitrary rule on par with private property. And while for small commodities such as toothbrushes, it's not particularly important that they are used after their sale, for productive means or land, this is quite an important aspect in order to prevent hoardism and usury.

Occupancy and use are no less arbitrary than other criteria. Take your toothbrush example (by no means the best for my purposes). Why daily? I can’t miss a day? How about a week if I forget it when packing for a trip? OTOH, why shouldn’t I have to use it twice or thrice daily? I’ve heard dentists say both. And what’s use? Of course brushing is, but what about dressing it up for little puppet shows for my niece or keeping it as a souvenir to look at every once and a while? What if I get joy just knowing it’s in my collection and never go near it? Occupancy is even more arbitrary. Do I have to occupy every square inch of what I occupy? Every square foot? Does occupying a perimeter occupy what’s within? How about what’s beneath or above? Must I use only myself to occupy or can I occupy with what I’m using or I’ve accumulated? And how often must I occupy what I occupy? Daily again?

All criteria for ownership is human based and therefore arbitrary. Some are simply more intuitive and/or better than others. Occupancy and use is simply humans cannot avoid as it limited by the laws of physics. I.e. two humans cannot occupy the same space at the same time. Therefore using the lowest common ownership claim which is self-evident as the maximum limit for ownership makes sense intuitively and it can be argued that it makes sense from an utilitarian perspective.

The truth value of the statement "two humans cannot occupy the same space at the same time" depends on the size of the space. Only if the space is smaller than x+y (x = the size of the smallest person, y the second smallest) is the statement true. Obviously, I don't believe one person should be able to nonconsensually occupy the same small space another person actually needs to occupy exclusively (the one currently occupied by his body), for that would literally be an act of violence (although not even violence is prohibited by the "laws of physics"). But by "occupancy", you're likely referring to a much larger, more lasting space. The idea that mutulaism is more intuitive is belied both by its small following and human history, which Bakunin understood better than Proudhon and Kropotkin better than both. As you look at your screen with your eyes and prepare to type with your fingers, notice that these are the frontiers of your brain's connection to its environment and that that computer is–indeed, according to science–no more your appendage than I am.

Again, I'm not arguing for mutualism by mentioning occupancy and use but rather mentioning where the ownership claim of communism as well can be anchored in.

The point I'm, trying to make is that in the same way that two people cannot stand on the same location at the same time (violence or not) which provides us with a basis to say that humans should always be granted the right to own at least a location as wide as their person. So can a scientific argument that a human needs at least x amount of living space to feel comfortable be used as a basis to claim that all humans should own at least this amount of space (and optionally, no more) for themselves.

It goes similarly with use. In the same way that a particular productive mean cannot be used by two people at the same time, and the fact that people need to use productive means in order to live in a society and/or maintain emotional balance, can be used as a anchor to argue that people should own theproductive means they use primariyl. The fine details (time to abandonment for example) of these ownerships are not important for us to discuss as they can be set by the society those people function in.

Again, I'm not arguing for mutualism by mentioning occupancy and use but rather mentioning where the ownership claim of communism as well can be anchored in.

The point I'm, trying to make is that in the same way that two people cannot stand on the same location at the same time (violence or not) which provides us with a basis to say that humans should always be granted the right to own at least a location as wide as their person. So can a scientific argument that a human needs at least x amount of living space to feel comfortable be used as a basis to claim that all humans should own at least this amount of space (and optionally, no more) for themselves.

It goes similarly with use. In the same way that a particular productive mean cannot be used by two people at the same time, and the fact that people need to use productive means in order to live in a society and/or maintain emotional balance, can be used as a anchor to argue that people should own theproductive means they use primariyl. The fine details (time to abandonment for example) of these ownerships are not important for us to discuss as they can be set by the society those people function in.

If there be a scientific argument for "that a human needs x amount of living space to feel comfortable", please identify it, along with the value of x and your meaning of the quite relative "comfortable". Your need to delegate these questions to society in order to avoid sounding like an arbitrary dictator is evidence that they aren't "intuitive" at all. Also, it doesn't follow from that a person needs a certain amount of space that he needs to own that space. Accordingly, there is no "ownership claim of communism" involving anything beyond one's person (and often not even that).

Again, you claim "that a particular productive mean cannot be used by two people at the same time", so apparently my correction went unnoticed. Here, I'll try an example: the two-man saw.

I believe this is self-evident to any human being. We may or may not know the X (I haven't looked) but this doesn't mean an X doesn't exist. I would define comfortable as the amount that does not create emotional pain of any kind. For example, it's pretty obvious that no human can be comfortable living in a space of 3×3. Therefore the minimum of X certainly is larger than this.

I never said that these are questions for me to decide on. I would rely on society listening to science in fact.

It can't follow from the is/ought dichotomy but it can be argued from a utilitarian perspective. (eg. Humans need a personal amount of space equal to x in order to avoid emotional pain. A personal amount of space can be considered to be owned or else they do not have the last word for it and it's not personal anymore as it can be violated by those who do have the last word. Therefore each person should have x amount of space owned in order to maximize utility)

You’re the one arguing for ownership. I’m against it; I think the appropriate living space for each person is infinity-by-infinity-by-infinity. It doesn’t follow from that that some would be suffocated by others. Under Parecon, if you want a certain space to be just yours, put it in your consumption plan, or, if it’s a workspace, production plan. (You will have to pay for it, if consumption, or otherwise use it to produce something of sufficient value of course.) But the idea that everyone needs space that’s just theirs is bourgeois nonsense. I, for one, have ample time to myself despite the fact that I have no space that’s just mine. I’m alone this instant, in fact, and, in a matter of hours, someone else will be alone in this exact room. That you “haven’t looked” is necessitated by the fact that there’s nothing to look at, nothing scientific at least.

You confuse the concept of having a space to be your own (where you store your personal stuff and you can return to rest) with the idea that you have pooled this space with others or that you have visitors. The fact that you can pool your personal space with others does not change the fact that when divided it's likely to be a particular amount between you.

In any case, I have no need to convince you on this. We can agree to disagree and whoever is perusing this dicussion can make their own decision.

For someone who calls others arrogant, you sure preface a lot of your comments with "you confuse the concept…" or "you mistake…" or similar. It's as if the idea that you might be the confused or mistaken one has never crossed your mind. Ironically, you didn't actually mean I confuse the two ideas; you meant that I mistakenly think the second belies the first, which is mistaken in and of itself, which makes the sentence doubly confusing. In particular, putting “(where you store your personal stuff and you can return to rest)” after “space to be your own” does not make the former dependent on the latter. Ownership is definitively authoritative, which you elsewhere seemed to understand, most immediately previously with “having the last word”. In reality, I have neither the last word nor any other, and I’m none the emotionally more hurt for it.

As I said, you have not the last word because you have freely decided to pool your claim with others for a more beneficial collective result. A person who was forced to collectivize as you seem to suggest however would have quite a lot of emotional pain because of this and the way it stepped on his individualism.

As such, you did have the last word and you chose freely to make it the last word of the collective instead. If one day you chose you wanted to have your own place instead again, one would assume you'd be allowed to have it rather than only have a choice of communal living spaces.

But I never owned individual space to begin with and have never wanted to. So obviously the need for individual space is no more universal than the need for collective space. Thus, guaranteeing minimal ownership of individual space is no more reasonable than guaranteeing minimal ownership of collective space. Thus, Parecon’s opt-out collectivism is as reasonable as your opt-in collectivism. The difference is of course that Parecon’s minimum is an equal share as opposed to an arbitrary “needed” one and the rest being decided by the majority, once and forever, at whatever time is arbitrarily designated the beginning of the revolution, either coercively or inspired by capitalism or at least its choices of possessors.

Of course we disagree on the question of whether to prepare and permanently allocate billions of x-sized living spaces; that‘s my point. If it were an uncontroversial proposal, it would perhaps be justifiable within our time (though still a crime against the future); however, otherwise it would be tyranny of the majority or worse.

It's not tyrrany of the majority to allow an anarchist society which has decided to allow workers to retain ownership of the factories they worked in and the houses they lived in. This is the reason why they would revolt in the first place more likely. To the switch things post-revolution and force them to collectivize for "the good of society" because a small minority claims this, is in fact the true tyranny.

What's this "retain"? They never owned them in the first place. In fact, because property is theft in the historical sense, possessors are possessors of stolen property, which is a crime in and of itself, and so are these "anarchists'" act of theft of authority without destroying it. The "small minority" of workers in labor-intensive industries and homeless and jobless folk would have much more to gain from a system which didn't allocate, a priori, power in proportion to how capital-intensive an industry capitalists and landlords selected one for and how big a house one could purchase with the money you correctly identify as illegitimate.

Ownership, incidentally, is the antithesis of free access, so once again, I recommend you study the differences between communism and mutualism, particularly the total lack of positive references to ownership made by the anarcho-communist Kropotkin. And what difference does post- or pre-revolution make? Any revolution will be post- many revolutions, all, like the dispute between possessors and capitalists, mere disputes between privileged classes. No, it would not be very anarchistic at all for the collectivists, even if a minority (again, see Kropotkin), to take any unscientific claims of ownership seriously.

So once again you’ve left a question up to society that society has neither the need nor the right to answer (even if the majority wanted everyone to own x-by-y-by-z living spaces, they would’ve failed to pass the affectedness test). I, for example, have no emotional pain that can be alleviated by owning space, so why should I be punished a priori with prohibition of access to part of my world? If not having exclusive space causes you more emotional pain than being excluded causes me, we should be able to prove it in trade.

I'd rather not, for trade would simply benefit the more economically powerful. I prefer a society which provides according to people's needs and since I expect that most people except the very few like you, require some personal space, I expect a common agreement to be reached to provide this. That you have emotional pain when not having unrestricted access everywhere is as much a concern to me as the capitalist who has emotional pain when he can't have 4 villas and 3 private jets.

Under Parecon, there are no economically more or less powerful. If personal space is truly a near-general need, it will be proven so through reiterated plans, not through some vote in which one has no incentive to distinguish wants from needs.

They have an incentive to distinguish wants from needs because it's their needs that they're voting on. People voting that everyone should have an X amount of space at least (Which they are allows to pool together into collectives of course) guarantess that they, themselves, will have an X amount of space, at least.

Yes, but some people value a guarantee of X amount of personal space less than others (I.e. one who doesn’t value space highly or already has a lot of space or fears they‘ll not be able to collectivize their new space favorably). And the less space that’s guaranteed to each individual, the larger, harder to occupy, and more varied in use the remaining spaces will be, which will, again, affect some differently than others. So, for some, the question of whether to guarantee X amount of space might be a coin toss (the utility of the guarantee is close to the disutility of the loss of social space), whereas for others it might be hugely important. Why should the coin toss people get an equal vote when the outcome barely affects them? Such fetishism of fairness might well effect an outcome contrary to social utility. Instead, put all space on the “market” and allow people to prove their affectedness by bidding with labor credits. This also avoids the problem of, once X amount of land has been decided, figuring out how to distribute the non-commodity.

You miss the point. the two-man saw cannot be used by 4 people at the same time. My argument is that an x-person productive mean cannot be used at the same time by x+1 or more people.

You missed two of mine: there are {x, >x}-person means, and there are transformations of x-person means into >x person means. For example (of the former), jumbo jets can be flown with one pilot, but a copilot makes it easier and safer. Under a possession principle, the pilot would be discouraged from taking on a copilot by the fact that it would mean losing half his property. Under Parecon or even capitalism, the pilot would only be paid for his effort and sacrifice and/or the market value of his labor (still quite a lot), without such irrational disincentives.

In a moneyless society it makes no sense for the pilot to risk his and his passengers safety just so that he can be considered to own the plane alone. What would be the point? He can't trade it for money anyway.

In a market economy, a plane owner who avoiding sharing the plane would be punished by the market by being avoided by customers due to safety risks. That is without considering that it would be impossible for one person to own a plane by himself anyway and it's likely to be owned by an airport/flights collective in the first place.

I can keep skewering your rigged examples the whole day. It will not change the fact that means of production have a physical limitation based on use and this can be then used as an anchor for ownership which prevents accumulation and inequality, i.e. possession.

Money is just currency. He could barter.

It makes little difference whether the enterprise is an individual plane or a vast, even monopolistic collective. The point is, in addition to the pretension of ownership being illegitimate, that the personnel level is such that adding one more would be worth the wages or credits dictated by a free labor price mechanism but not adding one to the denominator of the individual share. If it's easier, replace "copilot" with "janitor".

I can't believe you actually called it "skewering" to simply name the market reaction that was ALREADY IMPLIED BY MY SPECIFYING THAT HE WOULD BE WORTH THE WAGE OR CREDITS. The key is HOW MUCH will they be "punished"? All I “rigged” was profit-over-firm-size being higher than wages, a generic assumption, especially for capital-intensive firms like “airport/flight collectives”. From there, I simply cut to the chase, but we could do long division if that‘s what you need. So say that prospective member is worth giving him a share and is accepted into the collective. The firm size is now closer to ideal, meaning the “punishment” for failing to increase in size again will be less. The pattern would continue until the wage/share exceeded “punishment. Well, if a share’s better than a wage, the collective reaches that point sooner.

First of all, I don't see how forcing a collective to take more member because the managerial class decreed so for the "good of the community" is a better alternative. Second of all, you insist implying that there would be some profit motive for the company which would make its workers unwilling to expand in order to avoid dividing the share. But as I explained in communism the profit motive does not exist and in a mutualist economy the competition will make sure that people would add more quality to draw more customers.

If you're sayig that close to perfection a mutualist company might choose not to add extra members to avoid further diluting their shares, I'd say a close to perfection company is good enough and I doubt that parecon would be able to cover this little distance to perfection. That's just wishful thinking.

You say you don’t have to familiarize yourself with a theory in order to reject it, and then you continue making things up about Parecon. The sizes of the collectives are determined by the collectives, not the facilitators. As for competition, your faith in it is astounding. It can’t produce an infinite workforce, can it? Because that’s what would be needed for the need for “quality” to effect an optimal distribution of labor-to-capital ratios. From what I understand, communism’s non-competition and mutualism’s competition will save the day. How’s that work? Is there a medium level of competition that wouldn’t?

Money is just currency. He could barter.

It makes little difference whether the enterprise is an individual plane or a vast, even monopolistic collective. The point is, in addition to the pretension of ownership being illegitimate, that the personnel level is such that adding one more would be worth the wages or credits dictated by a free labor price mechanism but not adding one to the denominator of the individual share. If it's easier, replace "copilot" with "janitor".

For what? A moneyless society is not moneyless because currency has been banned. It's moneyless because it's unnecessary. What would a pilot trade for which would make up for the fact of not being a pilot anymore (i.e. not doing what he wants) and why wouldn't he simply do it without a trade?

I meant he could barter the service, not the plane. He could barter the plane, too, though, without losing his job, particularly if he bartered it for membership in a collective, thereby reducing competition, unfortunately for passengers and their dependents. Even if he did lose his job, many pilots would quit their careers this instant in exchange for what a plane could get them.

Again, that a problem of basing your system on money and wages rather than a communal way, where adding one extra worker when needed would be good if it allows a better working environment, more safety and even more creativity and fun due to the extra minds on the task.

Again, even in a mutualist society, theoretically adding people would make sense when required would make sense as it would make them more competitive. For example, the cleanest airports (those with more janitors) would make people want to go there instead. But it's an imperfect mechanism and it may end up to a drive to the bottom which is why I think communism is better.

Part of the imperfection is that it’s only temporary, pre-monopoly. And while increased competition would increase the demand for labor, it would seem to do so rather generally, not specific to capital-intensive industry, hence the problem I identified holds.

As for the “communal way“, labor would generally be immobilized by the absence of wages and currency (not coupled with abolition of property) and, if you’re correct, generally mobilized by possessors’ newfound love of company and disregard for profit, but that would not solve the specific problem of, again, the polarization of industry into very capital-intensive and very labor-intensive sectors.

Also, there's the matter of the original topic. The plane is a two-person means that can be used by one person. More importantly, any any-person mean can be turned into any any-other-person mean so long as it consists of as much of the same physical elements. In that sense, even such means have means, which only those actively engaged in such transformations are using productively. At any rate, that a mean can only be used by one at a time wouldn't justify ownership anyway.

That doesn't counter the point that a given productive mean can only have x workers assigned to it during any given period of time. During this time, those workers can be said to own this means of production.

Consumable Commodities are not so important, in other words, non-productive means, are not very important. A society may choose to say that such commodities can be considered to be "in-use" based on common sense. I.e. a toothbrush will be owned forever once taken (unless explicitly discarded) given hygienic reasons and its low cost. More expensive commodities which not everyone can have due to production limitations, may be agreed that are considered unowned based on some other limits. This is all up to the community in question.

Productive means (including land and living space) are much more important. Again, they are subject to community rule but this rule will be based on utilitarian reasoning grounded in occupancy and use. For example common sense would declare that a factory would be owned collectively by all its workers first, by the community it is in second and by the society as a whole third. This is only natural as the workers would have the most important voice on how the factory is run. The community around them would have the most important voice after the workers given its proximity to the externalities produced by the factory, and society as a whole would have last say given important need to co-operation.

If you mean post-allocation, I could barely agree more. In fact, a not bad system would be something like the Estates General, with the workers collectively, consumers collectively, and community collectively each getting a vote, with the rest of society having nothing to do with it. However, pre-allocation I see no reason why the power shouldn't be completely in society's hands. Having been selected by capitalists (or, later, having been selected by those selected by capitalists) and willing to work for their wages in a space is no indication of a group's expertise at deciding the most socially utilitarian future of it.

I'm not arguing for it. I am arguing that once a collective decision has been reached for the use of a space and the people found who volunteered to work it, then these people have the first say on how this use is done. In short, it does not fall to the society as a whole to micromanage those people. These people, by their use of that space, can be said to own it but they have also discovered that it's in their best interest to pass part of the decision making for this space (specifically the macro-management of it) to the society. But this follows from their ownership as it needs to be voluntary. I would oppose any society of forcibly collectivizing any workspace.